But buybacks occur at huge losses for investors. Today it bought back a 1.25% 20-year bond for 66 cents on the dollar.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

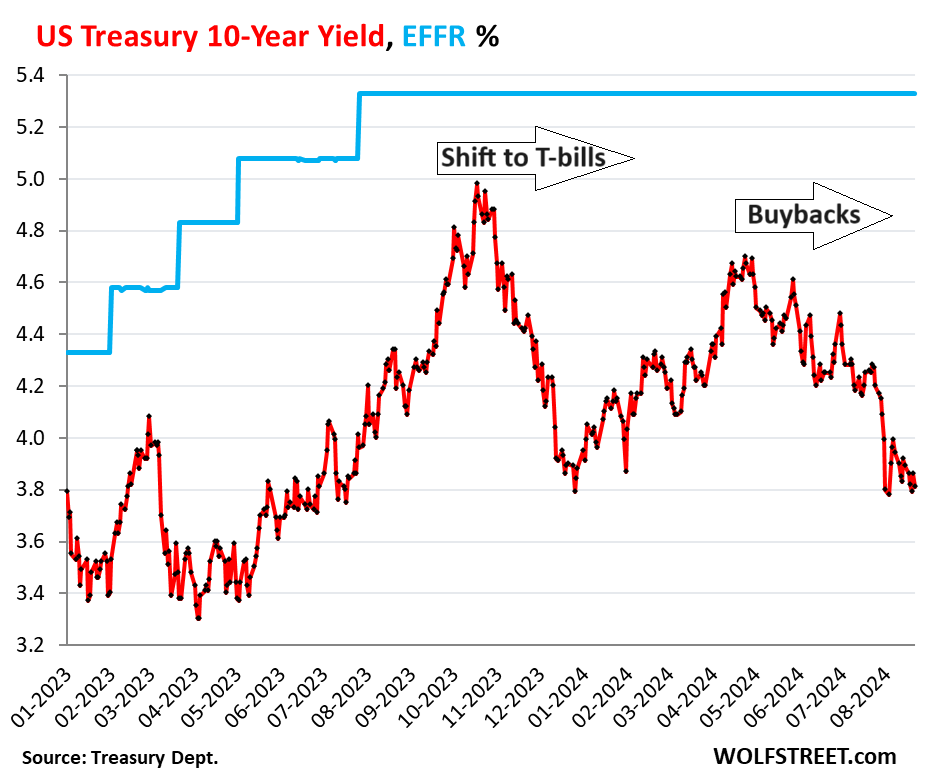

The US Treasury Department has been doing two major things to aggressively push down long-term yields on US government debt, and thereby long-term interest rates in the economy, such as for corporate bonds and mortgages:

- Shifting a larger portion of issuance of new debt to short-term Treasury bills, instead of longer-term notes and bonds, thereby increasing the proportion of T-bills outstanding.

- Buying back older longer-term Treasury securities with the proceeds from issuing new Treasury securities, so essentially replacing old securities with new securities, which doesn’t involve money creation and is not QE, but a swap of securities. It does put a big regular buyer into the harder-to-trade end of the bond market.

We can see the effects of those two policies on the 10-year yield. The increased portion of T-bill issuance starting in the second half of 2023 took pressure off the 10-year yield, which had been spiking into October 2023 and briefly kissed 5%. The buybacks, which started in April, coincided with a decline in the 10-year yield of nearly 100 basis points, even as the Fed was pushing back against rate-cut mania.

Adding more inflationary fuel to the economy.

Since the Treasury Department started this shift last year, T-bills – bracketed by expectations of the Fed’s policy rates – have yielded above 5%, substantially higher than the 10-year yield, which has ranged from 3.8% to just under 5% over this period.

So short-term, this strategy costs the government and taxpayers more money, but long term, if the bet works out, Treasury would reduce the effects of locking in the higher interest rates (interest expense!) on its incredibly ballooning debt for many years to come. But we doubt that saving the taxpayer money years in the future after this administration is long gone is the objective here. No one ever tries to save the taxpayer money.

The primary objective is clearly to manipulate long-term interest rates lower to stimulate the economy since long-term interest rates matter to the economy much more than short-term interest rates.

These lower long-term yields contribute inflationary fuel to the economy. They reduce mortgage rates. They encourage corporate leverage. They loosen financial conditions. This comes on top of the vast deficit spending, which also adds inflationary fuel to the economy.

These efforts by Treasury to push down long-term interest rates are in direct conflict with what the Fed has been trying to accomplish since it began hiking its policy rates.

The shift to T-bills.

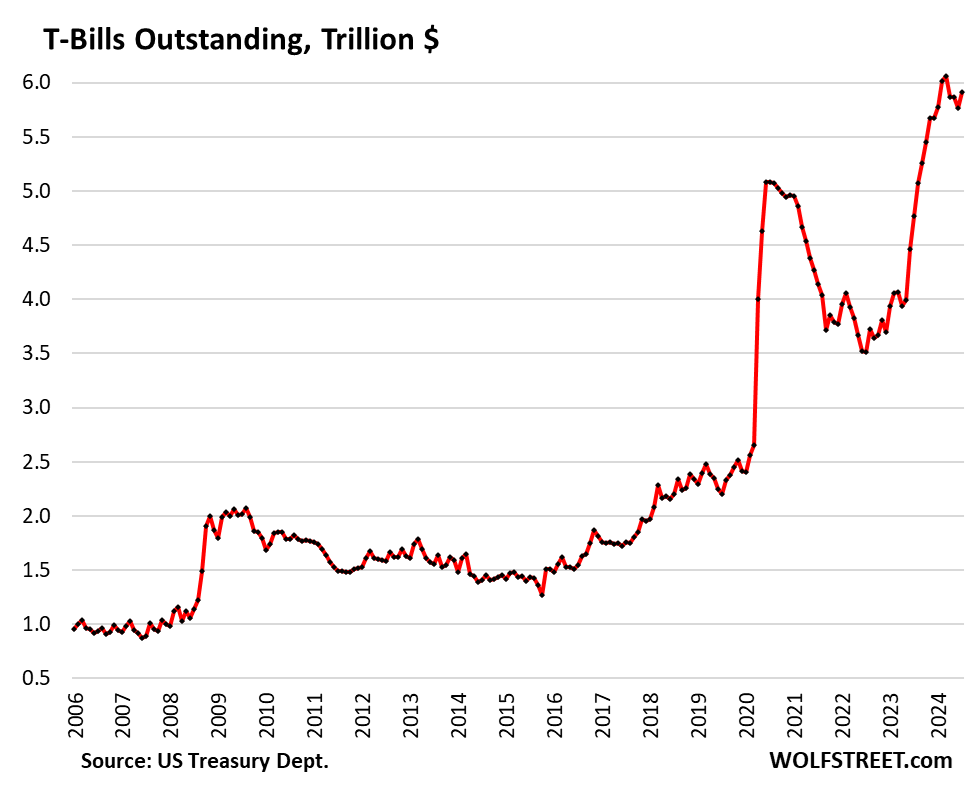

T-bill issuance has exploded since the debt ceiling was suspended in June 2023, and total T-bills outstanding spiked in 12 months by $2 trillion, or by 50%, from $4.0 trillion in March 2023, to over $6 trillion in March 2024.

Tax Day this year brought in a record amount of cash by mid-April, so T-bill issuance slowed in April through July. The outstanding amount in T-bills at the end of July was $5.9 trillion.

T-bills yields are bracketed by expectations of Fed’s policy rates and are not much influenced by issuance. There has been huge demand for T-bills.

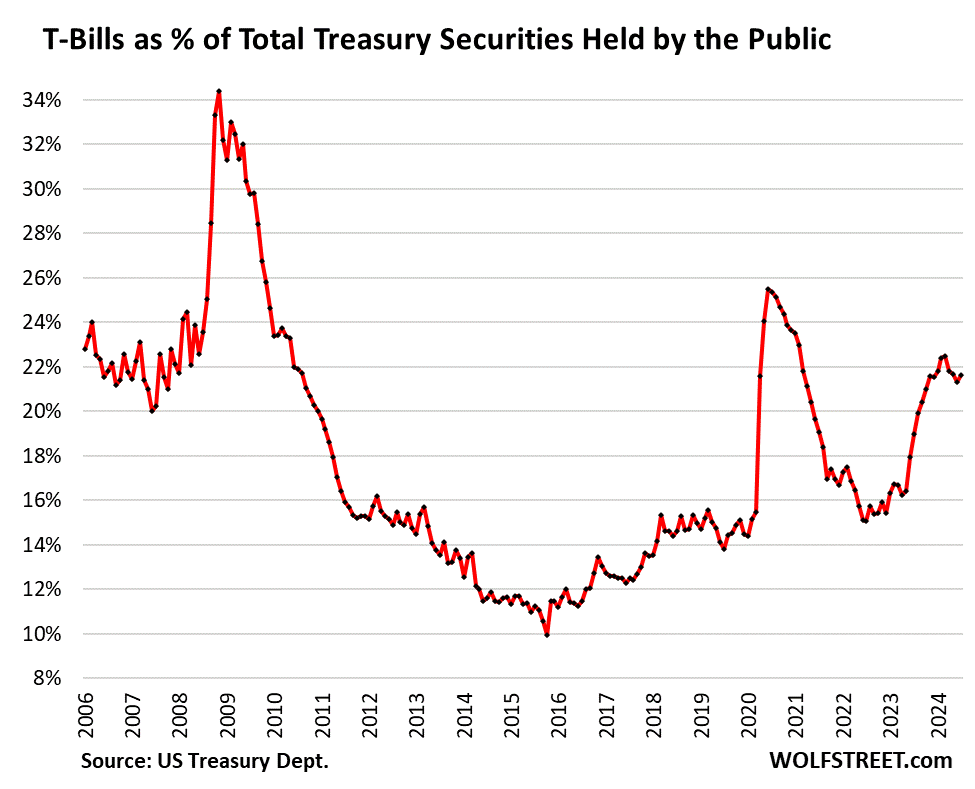

Between March 2023 and May 2024, the share of T-bills outstanding jumped from 16.7% of total marketable Treasury securities to 22.5% in March 2024. The record receipts around Tax Day relieved some of the pressure. But in July, the share started ticking up again. This is the shift to T-bills:

The shift to T-bill issuance is a bet that long-term interest rates would be lower over the next few years than they’d been in 2023 and 2024, and that the government could refinance those T-bills with lower-rate long-term debt. It’s thereby a (courageous?) bet that inflation will just quietly go back to 2%.

Treasury Secretary Yellen was infamously wrong about these inflation bets before, including in January 2022, when she said that she expected inflation to go back to 2% by the end of 2022. But 12 months later, the December 2022 reading of the core PCE price index, the Fed’s preferred measure for its 2% target, came in at 4.9% and core CPI at 5.7%. Inflation is hard to just wish away.

Buybacks are an even more aggressive move.

Under the buyback program, Treasury is buying back older “off-the-run” Treasury securities with the proceeds from issuing new Treasury securities, so swapping off-the-run securities for new on-the-run securities. This is essentially a swap of securities and doesn’t involve money creation and is not QE.

But it does add a big relentless bid to a portion of the Treasury market where liquidity can be thin, and where an investor that needs to unload a pile of off-the-run securities could do so only at a substantial discount compared to on-the-run securities.

By Treasury stepping into this end of the market, it is adding liquidity and its relentless weekly bid has the effect of lowering long-term yields. It started discussing this last fall and kicked it off in April, at first with smaller weekly auctions (on Wednesdays) that then increased in size. In recent weekly auctions it bought back between $2 billion and $4 billion.

Investors lock in massive losses.

At today’s auction, treasury bought back $2 billion in bonds. All bonds it bought back today have maturity dates between 2040 and 2042.

For example: 66 cents on the dollar. One of the eight bond issues that Treasury bought back today was $110 million of 20-year bonds (CUSIP 912810SR0), with a 1.25% coupon. The bonds had been issued in June 2020 when long-term yields had hit rock bottom.

Today, the 20-year yield is 4.22%. A 20-year bond that was issued four years ago, and has therefore 16 years left before maturity, trades like a 16-year bond, not a 20-year bond, and the 16-year yield would be lower than the 20-year yield.

Treasury bought back this 20-year bond at 65.64 cents on the dollar, in other words, at a discount of 34.36% to face value. Alternatively, the investor could have held it to maturity, collect 1.25% in coupon interest per year for 16 years, and then get 100 cents on the dollar.

For example, 77 cents on the dollar. Another of the eight bond issues that Treasury bought back today was $599 million of a 20-year bond with a 2.375% coupon, issued in March 2022. The price: 77.376 cents on the dollar, or a discount of 22.64% of face value.

The bonds that the government repurchased are then retired. The cash used to purchase those bonds has to be raised from selling new bonds, and so effectively, these older bonds are replaced by new securities.

These buybacks allow big investors, such as banks, to sell off-the-run long-term bonds at massive losses, but without further pushing down prices and pushing up yields, and without therefore further increasing their losses. This has the effect of propping up long-term bond prices and pushing down their yields – which then translates into lower interest rates in the economy.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()