By Rebecca Ray

In recent years, China’s engagement with Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) may be shifting in form and deepening rather than diminishing.

This is one of the key findings of the China-Latin America and the Caribbean Economic Bulletin, 2024 Edition, produced by the Boston University Global Development Policy Center. Indeed, we find that in 2023, a surge in diplomacy lay the groundwork for Chinese firms’ continued expansion of investment and infrastructure in the region.

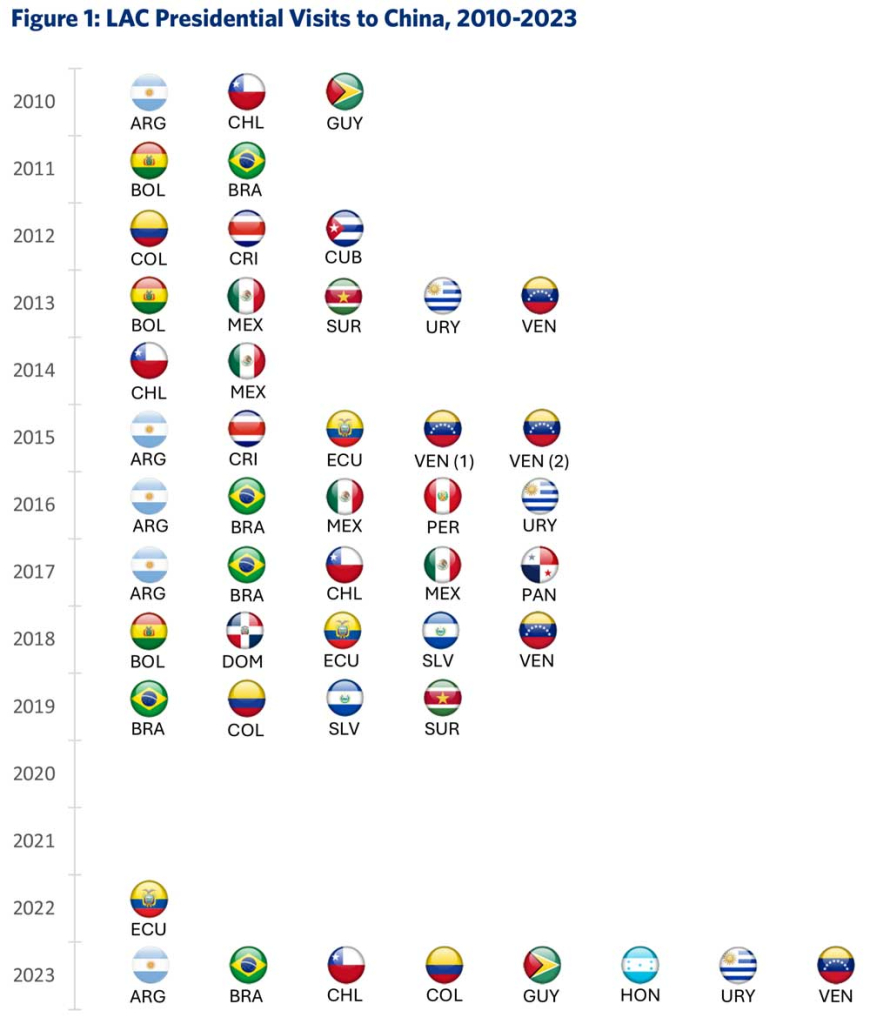

A record eight LAC presidents visited China in 2023, after just one visit in 2022 and none in 2020 or 2021, as Figure 1 shows. Previously, no year had seen more than five LAC presidential visits to China. In these trips, LAC leaders delineated their own visions and priorities for their countries’ relationships with China. Frequent agenda items included telecommunications (highlighted in all eight visits), commodity exports (which featured in six visits), and infrastructure and renewable energy supply chains (both featured in five visits).

Note: ARG: Argentina; BOL: Bolivia; BRA: Brazil; CHL: Chile; COL: Colombia; CRI: Costa Rica; CUB: Cuba; DOM: Dominican Republic; ECU: Ecuador; GUY: Guyana; MEX: Mexico; PAN: Panama; PER: Peru; SLV: El Salvador; SUR: Suriname; URY: Uruguay; VEN: Venezuela

These priorities are borne out in the relationship’s economic reality. Commodity exports—including traditional agricultural and mineral exports as well as newly relevant transition minerals—continue to grow in importance. Additionally, Chinese firms’ provision of infrastructure in LAC has risen significantly in recent years.

In particular, the 2024 China-LAC Bulletin highlights the rising importance of three sectors: agricultural commodities such as beef and soy, transition minerals such as lithium and copper, and rail infrastructure. Each of these sectors has very different implications for the long-term sustainable development prospects of the LAC region. For example, rail infrastructure—particularly urban passenger rail systems like the metro systems in Mexico and Colombia that Chinese firms are helping to build—can significantly improve curbing carbon emissions and improving quality of life in congested cities.

Agricultural commodities like beef and soy, on the other hand, are strongly linked to deforestation and environmental conflict, particularly in the major exporting country Brazil, although Chinese soy purchaser COFCO has signaled an interest in working more closely on agricultural supply chain sustainability. Transition mineral extraction can be developed in ways that lead to long-term project success and benefits for local economies or environmental harm leading to local economic losses and social conflict, depending on the oversight and protections applied, although significant work remains for establishing these frameworks for new sectors. Due to these sensitivities, then, continued diplomatic engagement is an encouraging sign for the development and oversight of future projects in these sectors.

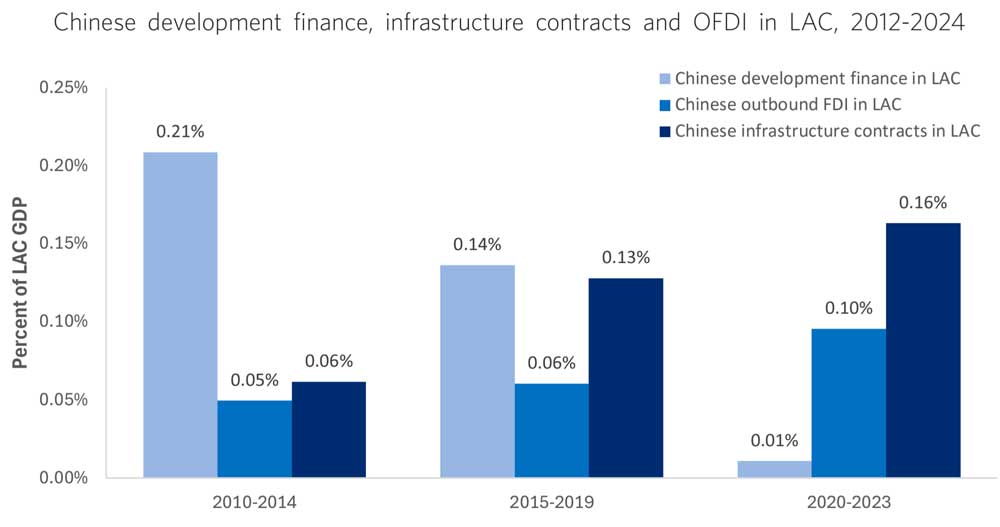

Although these sectors – infrastructure, and commodities – have long formed the backbone of the China-LAC relationship, the 2024 China-LAC Bulletin shows that the form of engagement has shifted significantly over the last decade. While China’s sovereign lending to the region has dried up substantially in recent years, as Figure 2 shows, it has largely been replaced with three major avenues forms of interaction – China-LAC economic engagement: Chinese development finance in LAC, provision of infrastructure in LAC and outbound foreign direct investment (OFDI) in LAC.

Figure 2 displays these trends in four-year periods, given the outsized impact of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic at the end of 2019. Over the last 12 years, Chinese development finance in LAC has fallen from 0.18 percent of regional gross domestic product (GDP) to just 0.01 percent. Concomitantly, Chinese firms’ direct provision of infrastructure has risen to 0.16 percent of regional GDP – nearly the same level as the heights of Chinese lending in earlier years. Furthermore, Chinese OFDI in LAC is now roughly twice the size of infrastructure provision, at 0.3 percent of regional GDP.

The Chinese infrastructure projects shown in Figure 2 always have a paying client (usually the host governments) and a provider firm. At times, the clients may use Chinese development finance to pay for these contracts, and in those cases, projects will be listed in both infrastructure and finance. However, infrastructure projects do not include any cases where Chinese firms take an equity stake, like COSCO’s port in Chancay, Peru, so they are not counted among Chinese OFDI.

Over the last 12 years, Chinese firms have deepened their direct engagement in the region, whether as project contractors or owners. In doing so, they are taking on greater commitments to the region, including exposures to longer-term project risks, further reinforcing the importance of active environmental and social risk management. Thus, shared environmental and social governance will continue to be a key policy priority in sectoral discussions.

Direct diplomacy—like the increasing number of direct presidential visits—will be a crucial avenue to ensuring that the relationship works for both sides’ long-term sustainable economic development goals.

Rebecca Ray, PhD, is a Senior Academic Researcher with the Boston University Global Development Policy Center. Follow her on X: @BUBeckyRay.