Sergei Chuyko/iStock via Getty Images

NEW YORK (August 13) – The “flash crash” that hit markets Monday, August 5th, is a looming symptom of what may well be an inexorable problem: the yen carry trade, or “YCT” as we’ll call it hereafter.

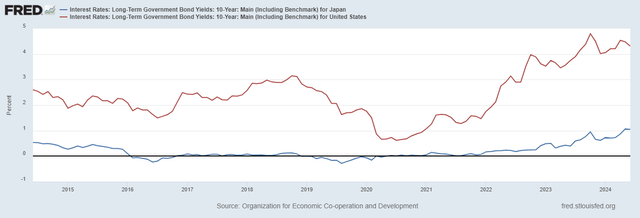

The theory of the YCT is very simple: the interest rate for Japanese Yen (JPY) has been around 1 percent – and near or below zero – for longer than decades. Meanwhile, as illustrated below, even at its lowest point in the past decade, the USD ten year bond was at least 61 bps above the JPY at its lowest point over that same period.

The YCT is obvious: borrow in JPY; then, convert the proceeds to USD and lend the borrowed funds at the higher US interest rates or invest them in risk assets in other markets (a number of hedge funds invested YCT in Mexican pesos, which were paying 10%). It’s a simple arbitrage, provided the USD/JPY pair is relatively stable, that had been largely low risk; a “no-brainer“, as some have characterized it. The YCT has fueled billions of liquidity into the US market. And nobody seems to know how much, exactly, because nobody seems to be tracking it.

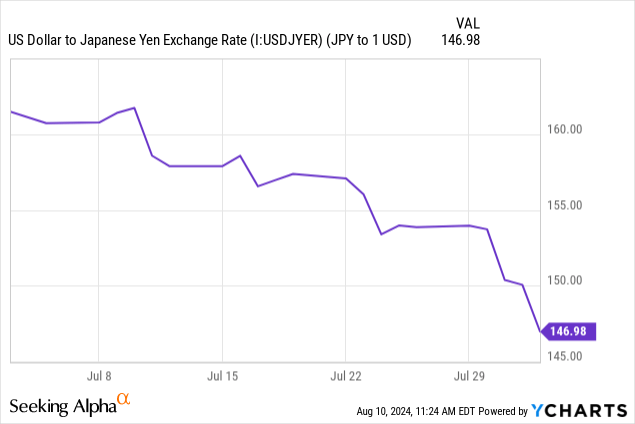

But on Wednesday, July 31st, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) raised rates and the JPY surged relative to the USD (“USD/JPY pair”) to its highest level since March. The effect can best be seen by this chart of USD/JPY of the month immediately before the formal BOJ rate increase, showing how fewer JPY can be purchased for the USD. From July 4 to August 4, the

The f/x effect of BOJ rate increase was exacerbated by the US jobs numbers and unemployment rate released Friday, August 2. The higher unemployment rate triggered the Sahm Rule recession indicator we addressed here in our July jobs report.

Fears of recession triggered by the Sahm Rule led most to speculate that the Federal Reserve would cut US rates when the Open Market Committee (FOMC) meets again in September. The lower rate would make the USD less attactive to hold, thus further accelerating the decline in the USD/JPY f/x, making the JPY more expensive, relatively.

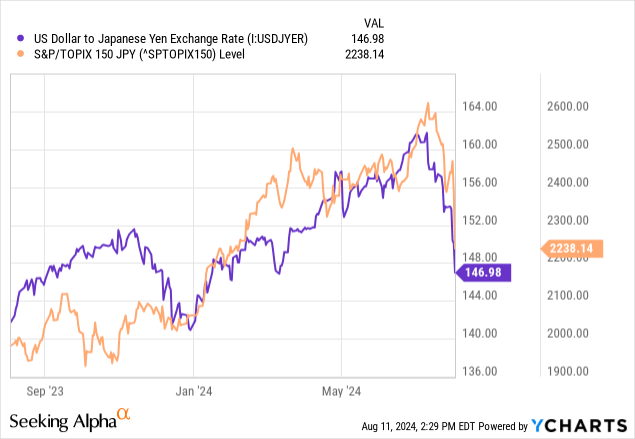

Last week’s surge in USD/JPY exchange rates (“f/x rates”), and fears the JPY would further appreciate, together with higher interest costs in JPY borrowing, drastically altered the risk portfolio for traders and investors in the YCT. Heavily leveraged traders and investors in the JCT, but also just Japanese invested overseas who were leveraged, were forced to sell off stocks to reduce their risk profiles and, in some instances, to meet margin calls. Meanwhile, as all this “unwinding” was occurring, demand for JPY was surging to settle them, further exacerbating the rise in the JPY in the USD/JPY pair.

The correlation with the appreciation of the JPY and the decline in the TOPIX, an index of leading Japanese companies, can be seen in the chart below.

A Glimpse of More to Come?

Last week’s flash crash may have just been a precursor of far worse to come. The BOJ tends to be much more opaque than the Fed, a circumstance that was noted by the financial press around this time last year when the BOJ slightly altered its decade-long effort at yield curve control. The cautious reaction to the move should have been a “warning shot” to the financial markets of Japan’s troubling rate circumstances and the efforts it will take to leg out of it.

Nobody really knows the size of the JCT. Estimates are all over the place, from $500 billion to $1 trillion and beyond. It’s recognized as substantial. Some of it was unwound last week. But we don’t know how much.

We do know this, though: the BOJ will do what is in Japan’s interest to do. So will the Fed. But things could go badly awry if the BOJ continues to normalize rates and the Fed continues to emphasize the “employment” side of its dual mandate to maintain full employment and stable prices and avoid recession by cutting rates. A misstep by either central bank could trigger a crash.

Last week, as markets were in sell-off, Wharton’s Jeremy Siegel urged the Fed to make an emergency 75 bps cut in interest rates. Siegel, who is also chief economist for Wisdom Tree, walked the suggestion back a few days later, but imagine what would have happened had Chair Powell, et. al., taken him up on his suggestion?

The USD would have sold off, making the JPY more expensive and further exacerbating the USD/JPY f/x risk of the YCT and forcing a greater sell-off. Simultaneously, traders legging out of the JCT would have upped demand for the JPY, turbocharging the JPY value relative to the USD even more.

What could have happened – and could still happen unless the Fed and the BOJ carefully coordinate their actions to address their respective priorities – is a “doom loop” with the price of JPY in the USD/JPY f/x pair accelerating and the Fed adding liquidity to stabilize US markets as traders move to cover their JPY borrowings. But doing so would only boost the relative value of the JPY further, creating additional market stress and US market asset sales, requiring more liquidity and further boosting the relative value of the JPY.

And on and on until all the YCTs were closed out or moved to a more manageable level, circuit breakers are hit, or regulators stepped in by some means to arrest the market melt downs.

Last week, after the Nikkei had melted down in its worst rout since 1987, Shinichi Uchida, the BOJ Deputy Chair, ameliorated market concerns by saying it “will not hike interest rates when markets are unstable”. The comment ran directly counter to the views expressed for several months by BOJ Chair and monetary hawk Kazuo Ueda.

Some in Japan criticized Ueda, an academic, who has served as Chair only since April 2023, for his messaging; giving markets the impression that hikes would be rapid and escalating. They chalked it up to inexperience, as the BOJ Chair usually is a seasoned Ministry of Finance veteran more sensitive to market concerns than academics.

We’re of the view that there is a substantial carry trade still “out there” and that Japan will continue to step away from its near Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP) increasingly in months to come. Much of the policy was to ameliorate the market effects of early 1990s tobashi schemes, where loss-generating assets were said to “fly away” (tobashi means “fly”) to other companies, rather like Lehman Bros moved its loss assets off to other companies in its infamous “Repo 105” scheme that triggered the 2008 Financial Crisis. Other schemes were also hidden from investors.

It’s taken 30 years, but we believe those losses have effectively been amortized through Japan’s economy and that normal Japanese rates can return. As they do, US investors should exercise great caution. And US regulators should be taking proactive steps to avoid the next market crisis. The Fed should coordinate closely with the BOJ and vice versa.

Avoiding another “Great Recession” is far better than bailing out systemically important financial institutions and stepping in to regulate exorbitant levels of risk after the fact. Leaders need to step up.

_______________________________

NOTE: Our commentaries most often tend to be event-driven. They are mostly written from a public policy, economic, or political/geopolitical perspective. Some are written from a management consulting perspective for companies that we believe to be under-performing and include strategies that we would recommend where the companies are our clients. Others discuss new management strategies we believe will fail. This approach lends special value to contrarian investors to uncover potential opportunities in companies that are otherwise in a downturn. Opinions here with respect to whether to buy, sell, or hold such companies, however, assume the company will not change its current practices. If you like such views, click up to follow us.