India’s agriculture exports have risen 6.5%, from $35.2 billion in April-December 2023 to $37.5 billion in April-December 2024. That’s more than the 1.9% overall increase in the country’s merchandise exports for this period. That said, the difference is even starker in imports. While India’s total goods imports during April-December 2024 were 7.4% up over April-December 2023, there was an 18.7% rise in imports of farm produce (from $24.6 billion to $29.3 billion) for the same period.

The agricultural trade surplus has thus reduced from $10.6 billion in April-December 2023-24 to $8.2 billion for the corresponding nine months of the current fiscal (April-March).

Narrowing surplus

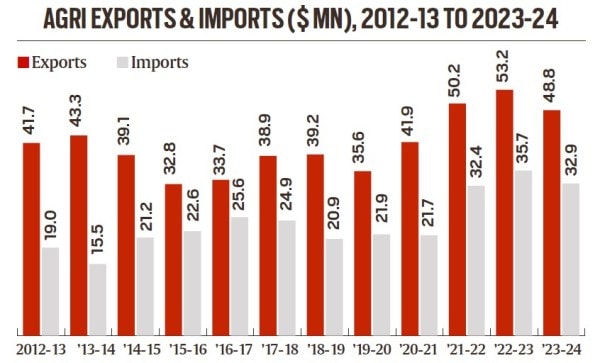

India is a net agri-commodities exporter, with the value of its outward shipments consistently exceeding imports (see chart). However, the trade surplus, which peaked at $27.7 billion in 2013-14, shrunk to $8.1 billion by 2016-17. It rose thereafter to $20.2 billion in 2020-21, before falling to $16 billion in 2023-24. It is set to further decline this fiscal.

The expansion or narrowing of the surplus has largely to do with exports. These dipped during the initial years of the Narendra Modi-led government, from $43.3 billion in 2013-14 to $35.6 billion in 2019-20, even as imports climbed from $15.5 billion to $21.9 billion. This was linked to a crash in international commodity prices.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) food price index (base period: 2014-16=100) plunged from an average of 119.1 to 96.4 points between 2013-14 and 2019-20. Low world prices made India’s agricultural exports less cost competitive, and its farmers more vulnerable to cheaper imports.

But the supply disruptions post the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine led to a global price recovery. As the benchmark FAO index soared to an average of 133.1 in 2021-22 and 140.6 points in 2022-23, India’s agri exports surged to $50.2 billion and $53.2 billion in these respective years. With the index easing somewhat after that, to 121.5 in 2023-24 and 123.4 in 2024-25 (April-January), exports, too, have come off their all-time-highs.

Drivers of exports

The accompanying tables show India’s top agricultural export and import items by dollar value. The No. 1 export commodity, marine products, has registered a drop from $7.8 billion in 2021-22 and $8.1 billion in 2022-23 to $7.4 billion in 2023-24. The fall has persisted in the ongoing fiscal as well.

Story continues below this ad

India’s marine exports — of which frozen shrimp accounts for roughly two-thirds — are mainly to the US (34.5% share in 2023-24), China (19.6%), and the European Union (14%). With the US being the biggest market, any move by President Donald Trump to impose tariffs can further hurt Indian seafood exports.

Sugar has also taken a hit, with exports more than halving from $5.8 billion in 2022-23 to $2.8 billion in 2023-24. Its exports, and also that of wheat (from $2.1 billion in 2021-22 and $1.5 billion in 2022-23 to hardly anything since), have suffered from government restrictions following concerns over domestic availability and food inflation.

Exports of rice have continued to boom. That includes non-basmati, on which the various curbs — from an outright ban on white rice to a 20% duty on parboiled grain shipments — have been gradually lifted. The ban on broken rice exports remains, but the value of non-basmati shipments is still poised to be quite close to its $6.1-6.4 billion highs of 2021-22 and 2022-23.

Exports of basmati rice — and also spices, coffee and tobacco — are likely to scale new records in 2024-25. Drought in Brazil and typhoon activity in Vietnam have given a boost to coffee exports from India. Crop failures in Brazil and Zimbabwe have, likewise, benefitted Indian tobacco exporters. India has also consolidated its position as the world’s leading exporter of basmati rice, chilli, mint products, cumin, turmeric, coriander, fennel, etc.

Drivers of imports

Story continues below this ad

India’s agricultural imports are dominated by two commodities: Edible oils and pulses.

Imports of pulses had come down considerably — from $3.9 billion in 2015-16 and $4.2 billion in 2016-17 to an average of $1.7 for the five years ending 2022-23 — on the back of increased domestic production. That underwent a reversal with a poor crop in 2023-24. The current fiscal could end with imports crossing $5 billion for the first time.

In edible oils, the outgo during 2024-25 is expected to be the highest after 2021-22 ($19 billion) and 2022-23 ($20.8 billion), which was basically courtesy of the war in Ukraine that drove up global prices.

In spices, India is both an exporter and an importer. In 2023-24, India’s imports of pepper (34,028 tonnes) and cardamom (9,084 tonnes) exceeded its corresponding exports of 17,890 tonnes and 7,449 tonnes. In other words, it was a net importer of these two traditional plantation spices. This, even as it has become a preeminent exporter of chilli and other non-traditional seed spices.

Story continues below this ad

As far as cotton goes, the Bt revolution — the planting of genetically modified hybrids — turned India into the world’s second largest exporter after the US. The country’s cotton exports were valued at $4.3 billion, $3.7 billion and $3.6 billion in 2011-12, 2012-13 and 2013-14 respectively. That has collapsed to $781.4 million in 2022-23 and $1.1 billion in 2023-24.

During April-December 2024, India’s cotton exports were, at $575.7 million, not only 8.1% lower than for the same period of 2023, but its imports of $918.7 million were up 84.2%. Thus, from an exporter, India is today a net importer of cotton.